My new e-mail address is jeffreyslaw@hotmail.com.

Thanks,

Amanda

Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Friday, January 20, 2006

Jeffrey's Birthday

Today would have been Jeffrey's 9th birthday. I donated some money to the local Humane Society in his name. Animals have so much in common, they don't expect anything in return for their unconditional love. ..

I wonder what yvonne and richard are thinking today... if they even remember.

It's such a contrast when my son's birthday is celebrated to the nines because it will always be the happiest day of my life, as I'm sure it is for all of you. I will never understand or sympathize with this people, I can't even be empathetic towards them because I can not relate at all. I can not put myself in their shoes. I suppose we might as well all give up trying to rationalize what happened and just keep waging the battle...

Happy birthday Jeffrey.

I wonder what yvonne and richard are thinking today... if they even remember.

It's such a contrast when my son's birthday is celebrated to the nines because it will always be the happiest day of my life, as I'm sure it is for all of you. I will never understand or sympathize with this people, I can't even be empathetic towards them because I can not relate at all. I can not put myself in their shoes. I suppose we might as well all give up trying to rationalize what happened and just keep waging the battle...

Happy birthday Jeffrey.

Public Rally

Therese suggested in one of her posts that we should hold a public (peaceful) protest / rally in front of the CCAS. I think it's a great idea, but like she mentioned, they will laugh if I show up there alone, so please let me know if you would be interested in attending and if there are enough of us, I will start making posters and contacting the media.

I was thinking Friday February 17th in the afternoon. I know a lot of you work during the week, hopefully you could get the afternoon off work though.

Let me know if you have any idea's for the posters.

I was thinking Friday February 17th in the afternoon. I know a lot of you work during the week, hopefully you could get the afternoon off work though.

Let me know if you have any idea's for the posters.

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Inquiry and some articles from 2003...

Although, in my opinion, an inquest is not very beneficial, I think that we should write to Dr. Jim Cairns and Dr. Barry McLellan urging them to call one immediately following the sentencing of bottineau and kidman.

If nothing else, the investigation may answer a lot of questions we have about why / how the CCAS failed Jeffrey and it would definitely publicly tarnish the organizations name.

26 Grenville Street

Toronto, ON M7A 2G9

416-314-4000

I also found two articles from 2003 that are very interesting. I have highlighted the key points:

CCAS: 'NO ROLE' IN CASE

AGENCY PROMISES 'RIGOUROUS STANCE' ON CAREGIVERS

Monday, March 24, 2003

BY ROB LAMBERTI, TORONTO SUN

The Catholic Childrens Aid Society is taking a "rigourous" stance in checking the backgrounds of aspiring caregivers following the death of an emaciated five-year-old Toronto boy.

Jeffrey Baldwin weighed just 19 pounds when he was rushed from his Woodfield Rd. home, where he lived with his grandparents, to the Hospital for Sick Children last November. The boy, who was allegedly kept locked in a room, was pronounced dead shortly after arrival, suffering from pneumonia.

The CCAS didn't oppose or approve a custody application for Jeffrey by his grandparents.

The couple are now accused of first-degree murder and forcible confinement. They're to appear in court Wednesday for a bail hearing.

Society spokesman Fernando Saldanha said the society regrets not checking its files, which showed that both grandparents had criminal records involving child abuse. Jeffrey's grandmom was sentenced to a year's probation in 1970 after her daughter died of pneumonia. His step-grandfather was convicted in 1978 for the assaults of two of his wife's children.

"If the records had been properly checked by the workers involved at the time, then the situation would have been very different."

A Toronto Sun story Thursday said the society allowed the children to stay with their grandmother despite the fact the society's own records showed she had a prior conviction of child assault. Saldanha said the society actually played "no role" in the granting of the children to the grandparents.

Saldanha said procedures are "much more rigourous in terms of doing a thorough check of all of the names of individuals coming forward ..."

******************************************

SOCIETY PROBED IN TOT'S DEATH

CRIMINAL RAPS EYED

Tuesday, March 25, 2003

BY ROB LAMBERTI, TORONTO SUN

Toronto homicide detectives are investigating the Catholic Children's Aid Society and an unspecified number of case workers to determine if there was any criminal negligence in the death of Jeffrey Baldwin.

The emaciated 5-year-old boy weighed 19 pounds when he died last Nov. 30. An autopsy showed Jeffrey died of pneumonia as a result of the debilitating state of his body.

The lad allegedly lived as a virtual prisoner in a room he shared with his 6-year-old sister. Sources described Jeffrey's body as having sunken eyes and cheeks, loose skin about the buttocks, sores on the buttocks and penis, and a distended belly. His legs and arms were described as sticks.

Two other siblings also lived in the Woodfield Rd. home, in the Gerrard St.-Coxwell Ave. area.

Det.-Sgt. Mike Davis wants to know why the agency had never checked the grandparents' files during any of three separate applications the couple made for the children between 1997 and 2000.

The grandparents' files contained records of previous incidents. The grandmother was sentenced to a year probation after tiny fractures were found in the body of her five-month-old child, who died of pneumonia in 1970. The grandfather was convicted in 1978 of beating two of his wife's other children.

Elva Bottineau, 52, and Norman Kidman, 51, are charged with first-degree murder and forcible confinement, and are to appear in court on Wednesday for a bail hearing.

"I'm looking at the agency and its workers with the possibility of criminal wrongdoing, vis a vis, criminal negligence causing the death of Jeffrey Baldwin, and criminal negligence causing bodily harm involving the other children," Davis said.

"They know it," he said, but added he's not certain if the agency realized he planned a criminal investigation rather than just gathering information for a possible inquest.

The agency and its staff are "not responsible" for the death, Davis said. "It's a parallel investigation. It's a different issue."

Jeffrey was awarded to his grandmom and step-granddad along with a sister in 1998.

The agency had neither approved nor opposed the grandparents' private applications for custody of the children, CCAS spokesman Fernando Saldanha said. But he said the society should have had a role in the grandparents' applications. He said the agency concentrated on the childrens' parents and the grandparents were not under scrutiny.

**********************************************************

So what happened?? Dt. Davis is now retired, so I don't know how to get a hold of him.

He testified at the trial because he interviewed james mills initially.

I would really like to know what the result of his investigation was, so if anyone knows how he may be contacted, please let me know.

Thank you.

If nothing else, the investigation may answer a lot of questions we have about why / how the CCAS failed Jeffrey and it would definitely publicly tarnish the organizations name.

26 Grenville Street

Toronto, ON M7A 2G9

416-314-4000

I also found two articles from 2003 that are very interesting. I have highlighted the key points:

CCAS: 'NO ROLE' IN CASE

AGENCY PROMISES 'RIGOUROUS STANCE' ON CAREGIVERS

Monday, March 24, 2003

BY ROB LAMBERTI, TORONTO SUN

The Catholic Childrens Aid Society is taking a "rigourous" stance in checking the backgrounds of aspiring caregivers following the death of an emaciated five-year-old Toronto boy.

Jeffrey Baldwin weighed just 19 pounds when he was rushed from his Woodfield Rd. home, where he lived with his grandparents, to the Hospital for Sick Children last November. The boy, who was allegedly kept locked in a room, was pronounced dead shortly after arrival, suffering from pneumonia.

The CCAS didn't oppose or approve a custody application for Jeffrey by his grandparents.

The couple are now accused of first-degree murder and forcible confinement. They're to appear in court Wednesday for a bail hearing.

Society spokesman Fernando Saldanha said the society regrets not checking its files, which showed that both grandparents had criminal records involving child abuse. Jeffrey's grandmom was sentenced to a year's probation in 1970 after her daughter died of pneumonia. His step-grandfather was convicted in 1978 for the assaults of two of his wife's children.

"If the records had been properly checked by the workers involved at the time, then the situation would have been very different."

A Toronto Sun story Thursday said the society allowed the children to stay with their grandmother despite the fact the society's own records showed she had a prior conviction of child assault. Saldanha said the society actually played "no role" in the granting of the children to the grandparents.

Saldanha said procedures are "much more rigourous in terms of doing a thorough check of all of the names of individuals coming forward ..."

******************************************

SOCIETY PROBED IN TOT'S DEATH

CRIMINAL RAPS EYED

Tuesday, March 25, 2003

BY ROB LAMBERTI, TORONTO SUN

Toronto homicide detectives are investigating the Catholic Children's Aid Society and an unspecified number of case workers to determine if there was any criminal negligence in the death of Jeffrey Baldwin.

The emaciated 5-year-old boy weighed 19 pounds when he died last Nov. 30. An autopsy showed Jeffrey died of pneumonia as a result of the debilitating state of his body.

The lad allegedly lived as a virtual prisoner in a room he shared with his 6-year-old sister. Sources described Jeffrey's body as having sunken eyes and cheeks, loose skin about the buttocks, sores on the buttocks and penis, and a distended belly. His legs and arms were described as sticks.

Two other siblings also lived in the Woodfield Rd. home, in the Gerrard St.-Coxwell Ave. area.

Det.-Sgt. Mike Davis wants to know why the agency had never checked the grandparents' files during any of three separate applications the couple made for the children between 1997 and 2000.

The grandparents' files contained records of previous incidents. The grandmother was sentenced to a year probation after tiny fractures were found in the body of her five-month-old child, who died of pneumonia in 1970. The grandfather was convicted in 1978 of beating two of his wife's other children.

Elva Bottineau, 52, and Norman Kidman, 51, are charged with first-degree murder and forcible confinement, and are to appear in court on Wednesday for a bail hearing.

"I'm looking at the agency and its workers with the possibility of criminal wrongdoing, vis a vis, criminal negligence causing the death of Jeffrey Baldwin, and criminal negligence causing bodily harm involving the other children," Davis said.

"They know it," he said, but added he's not certain if the agency realized he planned a criminal investigation rather than just gathering information for a possible inquest.

The agency and its staff are "not responsible" for the death, Davis said. "It's a parallel investigation. It's a different issue."

Jeffrey was awarded to his grandmom and step-granddad along with a sister in 1998.

The agency had neither approved nor opposed the grandparents' private applications for custody of the children, CCAS spokesman Fernando Saldanha said. But he said the society should have had a role in the grandparents' applications. He said the agency concentrated on the childrens' parents and the grandparents were not under scrutiny.

**********************************************************

So what happened?? Dt. Davis is now retired, so I don't know how to get a hold of him.

He testified at the trial because he interviewed james mills initially.

I would really like to know what the result of his investigation was, so if anyone knows how he may be contacted, please let me know.

Thank you.

Ordering a court transcript

If you would like to order a transcript of the Bottineau / Kidman trial (after sentencing) here is the information:

Fax your request to 416-327-5886

Include:

* Judges name: Honourable David Watt

* Date began and finished: September 9th, 2005 - February 16th, 2006 (exact date may be different)

* # of copies requested

* your name, address, phone number, etc.

I assume they will either fax back or call you about payment plus shipping which is probably by credit card.

You can not request a transcript until the criminals have been sentenced though.

Fax your request to 416-327-5886

Include:

* Judges name: Honourable David Watt

* Date began and finished: September 9th, 2005 - February 16th, 2006 (exact date may be different)

* # of copies requested

* your name, address, phone number, etc.

I assume they will either fax back or call you about payment plus shipping which is probably by credit card.

You can not request a transcript until the criminals have been sentenced though.

Jeffrey's short, tragic life

Jan. 18, 2006. 06:16 AM

NICK PRON

COURTS BUREAU

Jeffrey Baldwin was just a few weeks old and already he had a nickname.

Looking at the baby with the sweet smile and adorable blond ringlets, the proud father said the tight curls reminded him of popcorn. So he dubbed him “Jeffy Pops.”

“He was such a cutie,” Jeffrey’s grandmother, Susan Dimitriadis, recalled. “We all adored him.”

Less than six years later, little “Jeffy Pops” would be dead, starved of food and affection in what one doctor later described as possibly the worst case of child malnutrition ever seen in Canada.

Jeffrey’s short, tragic life can be told through snapshots taken by his father, Richard Baldwin, which he later gave to Dimitriadis. One shows him with his siblings at Christmas 2001, Jeffrey almost a head shorter than his younger brother.

The photos are all she has left to remind her of her doomed grandson, who later became the “invisible child in the middle room” at the east end home of his maternal grandparents, Elva Bottineau and Norman Kidman. Jeffrey died in the house near Gerrard St. E. and Greenwood Ave. on Nov. 30, 2002.

The couple was charged with first-degree murder, but proclaimed their innocence. Jeffrey was dim-witted, Kidman complained to the police, and couldn’t be toilet trained. He was damaged goods when they got custody, she said. Their four-month trial by judge alone ended yesterday. In his closing remarks, Bottineau’s lawyer Anil Kapoor said she never intended to kill Jeffrey and added that with her I.Q. of 69, she never thought that he might die.

Kidman was “grossly negligent” for doing nothing to help Jeffrey, and guilty of manslaughter but not murder, his lawyer Robert Richardson said in his final remarks to Mr. Justice David Watt, who will deliver his verdict on Feb. 16. If convicted, Bottineau, 54, and her common-law husband, Kidman, 53, could get life in prison.

Throughout the trial, Bottineau and Kidman sat expressionless while they listened to evidence that brought tears to the eyes of courtroom observers and left them wondering how a defenceless child could suffer such a terrible fate. How could a child starve to death in the heart of Canada’s richest city? Why did nobody come to his aid? Where was the Catholic Children’s Aid Society?

Those questions were never answered at the trial that offered some stark glimpses at the short, tragic life of Jeffrey Baldwin. In a brief moment of joy during an interview with the Toronto Star, Dimitriadis recalled the infant Jeffrey’s cheery little smile as she bounced the 10-pound baby boy on her lap shortly after he was born at Doctor’s hospital on Jan. 20, 1997.

Dimitriadis had never wanted her son, Richard, to become a father so soon, and definitely not with Yvonne Kidman. After all, both were still children themselves in 1994 when they first moved in together, he 17 and she 16.

The ill-fated union of the two teenagers would be a continuation of a cycle of abuse that dated back at least two generations in both families.

Dimitriadis had tried but couldn’t stop her strong-willed son when he dropped out of high school to get a job as a mover, then left home and moved in with Yvonne.

It was a volatile relationship from the start. In 1994, the Catholic Children’s Aid Society was called to investigate reports that a baby had been left alone by her squabbling parents. The couple was out in the street, screaming at each other while their first child, a daughter, was alone in the crib of their basement apartment.

It was recommended that the couple get counselling, and that Richard, who had a learning disability, get further therapy for anger management. He didn’t, and their daughter was later placed with Bottineau and Kidman by a court order.

Three years later, the baby Jeffrey appeared healthy and happy, even in the tumultuous home of his young parents. But there were signs that their fighting was affecting him. As soon as he was able to crawl, around seven months, Jeffrey started banging his head on the concrete floor of the basement apartment. A doctor told the couple Jeffrey would grow out of it.

Heavier than most babies at birth, Jeffrey was also taller than 97 per cent of infants his age, according to developmental charts. Had Jeffrey continued at the same rate of growth, he would have weighed about 44 pounds by his sixth birthday. When he died two months before he would have turned 6, he weighed just 21 pounds, about the body weight of a 10-month-old infant, and a pound less than his first birthday.

About a year after Jeffrey, their third child, was born, the couple had decided to split up. They have since got back together. It was agreed that Yvonne would take Jeffrey and his sister, and Richard would continue to pay support.

At the time, Bottineau was considered “an ally” of the Catholic Children’s Aid Society, a seemingly concerned grandparent trying to help her daughter and her common-law spouse sort through their difficulties. So there was no opposition from the society when Bottineau and Kidman got custody of two more of the couple’s children, Jeffrey and his sister.

In October 1999, when Yvonne had her fourth child, the boy was once again given to Bottineau and Kidman through a court order, and once again, there was no opposition from the society.

Initially, at least, the placement of the four children with the grandparents seemed to be working. Kidman took them for treats to McDonald’s restaurant, and reportedly “doted” on his grandchildren. Pictures show Jeffrey cuddling up to his grandad.

Neighbours recall seeing Bottineau walking about the neighbourhood with Jeffrey safely tucked into his stroller, a seemingly happy and well-fed child.

During arranged visits - a court had given Bottineau full authority over the children’s visitors - Dimitriadis remembered watching Jeffrey merrily playing trucks with his siblings in the livingroom of their new home. Or frolicking in the backyard on the swing set. A neighbour even wrote a letter of reference for Bottineau who wanted to look after other children. “The children are in good health and well cared for ... very happy-go-lucky kids,” the neighbour wrote Jennifer Noseworthy in the fall of 2000.

“I have witnessed the amount of love and affection the children get on a daily basis. I am very confident in the good care they are receiving. Elva should be congratulated on the way they have accepted and cared for the children.”

But there were signs of trouble in late 2000. A case worker with the Toronto Children’s Aid Society noticed Jeffrey had a bruise under an eye. It was passed off as an accident on the swings. The file was closed on Sept. 15, 2000 with the note: “No indication of imminent risk to the children.”

A year earlier, 1999 when she last saw the children, Dimitriadis recalled that it was a short, strained visit. Although her grandchildren were happily playing in the living room, she sensed there was trouble in the crowded, semi-detached dwelling, home to six children, six adults and a dog, Bear.

When Dimitriadis returned at Christmas, bringing presents, she had the door slammed in her face by Kidman who told her not to bother coming back. Dimitriadis complained to the Catholic Children’s Aid Society and was told that it was up to Bottineau to decide who saw the children.

Early in 2001, Dimitriadis got the first of what would be a string of disturbing pictures of Jeffrey. While her grandson still looked healthy, his cheery smile was gone.

“There’s something wrong with that child,” she told her son. “Why is there so much tension in his face?”

She was told he had a cold. The boy’s father complained that he never got to see Jeffrey that much either, and then only with the permission of Bottineau.

Behind the closed doors of the east end home a human tragedy was evolving. Jeffrey and a sister had become branded as “the bad ones” in the family, while his oldest sister and baby brother were known as “the good ones.”

Bottineau no longer took Jeffrey for walks around the neighbourhood. He was about to become the “invisible child,” the “freak,” while his next oldest sister was called “psycho.”

Bottineau once complained to a neighbour about being overwhelmed by the demands of raising four children. She was having trouble toilet training Jeffrey and his sister.

Despite having six kids of her own, raising four grandchildren and babysitting other youngsters in the neighbourhood, Bottineau was not comfortable around pre-pubescents.

While growing up in a town north of Toronto, Bottineau had watched helplessly as her alcoholic stepfather pushed her mother down the stairs and chased her around the house with an axe, once nearly cutting off a breast.

After leaving home at 16, Bottineau married a distant cousin, a union that resulted in three children. The couple’s first child, a four-month-old girl, died under suspicious circumstances. Bottineau was later convicted of assault causing bodily harm in the girl’s death. After divorcing her cousin, Bottineau’s subsequent common-law marriage to Kidman produced three more children, including Yvonne.

A psychological report submitted at the trial described Bottineau as having borderline intelligence and being quick-tempered, hostile and a “danger to herself and others.” She was an “incompetent parent” who was “incapable of coping” with the demands of children.

Kidman, a groundskeeper with Metro Housing, was also not comfortable in his role as a parent. He got “anxious and frustrated,” overwhelmed by the demands of children.

He let Elva set the rules for the family, and he was the enforcer. Disobey, and the children got a spanking, a whack on the head with a rolled up newspaper, a smack with a metal spoon.

Perhaps sensing she needed help, Bottineau once asked a neighbour if she wanted to adopt Jeffrey. The woman, with a newborn of her own, declined the offer.

By 2001, Jeffrey had become a “non-person,” the family’s little secret who stayed at home, hidden away from the world. He should have been getting ready for junior kindergarten. But since his grandparents had given up trying to toilet train the child, he never went to school.

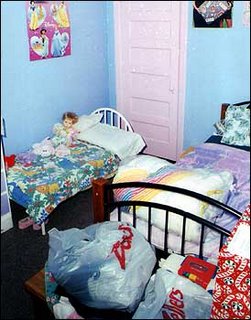

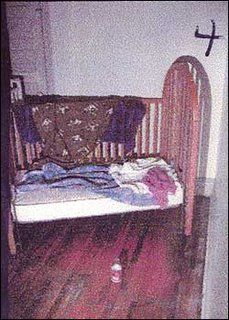

Jeffrey and his next oldest sister were banished to the middle bedroom of the second floor and locked in at night. The furnace vents to the room were closed. The room that was always cold, also served as their bathroom.

While his sister eventually got toilet-trained and went to school, Jeffrey was constantly being screamed at for soiling his pants, his bed and the floor around his crib.

His daily routine was always the same: After being freed from his bedroom around noon, he would be bathed to wash a night’s worth of fecal matter off his body.

Then he had lunch, eating out of a bowl with his hands, sitting on the floor in his designated spot on a rug by the door, dubbed the “pig corner.” He wasn’t fit to eat at the table with the other children, who wouldn’t play with him.

In the afternoons he was allowed to play by himself with toys belonging to his siblings. His favourite was trucks. Or he watched television while his grandmother chatted away on the Internet.

When Kidman returned home from work late in the afternoon to take over the television, parking himself in his La-Z-boy chair, Jeffrey was often ordered back to “his spot,” the dirty mat by the door, where he stayed until bedtime. Some days, when she was busy chatting on the Internet, Bottineau kept Jeffrey locked in his room all day, his cries to be let out ignored. Instead of affection, Jeffrey was ridiculed, and hit whenever people got frustrated with him.

When James Mills, an unemployed boyfriend of one of the couple’s daughters, moved into the house, he said he was there for nearly two weeks before he even saw the child.

Mills was in the kitchen when he heard a tiny voice, and swung around to see Jeffrey sitting in his spot by the wall. “Hello, James,” said Jeffrey. The boy who was called “the retard” was bright enough to have learned the newcomer’s name.

Mills was shocked at Jeffrey’s wasted frame and even though he suspected the child was dying, he never thought of going to the authorities for help.

Jeffrey was back in his locked room nightly by about 8 p.m. Toward the end, his body was so weak that it took him 10 minutes to get up the stairs. Nobody thought to help him. It was like he wasn’t there.

One summer evening when the other children were taken to the park to watch a fireworks display, Jeffrey stayed behind, locked in his bedroom. After the fireworks, his oldest sister returned, filled with childhood excitement at the explosions of colour she had witnessed that evening. She went up the stairs to Jeffrey’s bedroom, sat on the floor outside his room and called out his name.

Shivering in his damp room, Jeffrey listened through the door while she described the wonders he had missed. It was one of the rare displays of affection he would experience in his brief, painful life.

On Nov. 30, 2002, Bottineau called 911 to report a child not breathing. Emergency crews gasped when they first saw Jeffrey’s wasted body. He was all skin and bones, covered in sores with a scaly rash from sleeping in his own bodily wastes. He had more than a dozen distinct bruises and abrasions. His once-sparkling brown eyes were mere sink holes in his shrivelled-up face.

The official cause of death was septic shock, his body too weak from hunger to fight off the ravages of bacterial pneumonia.

Throughout the trial of Bottineau and Kidman, people cried unashamedly, flinching over eyewitness accounts of Jeffrey’s wretched existence, of how he drank water from the dog bowl or the toilet, or got a beating when he was slow cleaning his feces off the wall.

In murder trials, there is usually an undercurrent of anger against the accused, though they are presumed innocent until a judge or jury decides otherwise. In Jeffrey’s trial there was an added emotion - disgust.

Not only for the grandparents accused of his murder, but for the system which failed to protect a helpless child.

Throughout the trial, the finger of blame was pointed at the Catholic Chidren’s Aid Society for their part in the tragedy and their apparent reluctance to turn over files about the case.

That prompted a society lawyer to step forward, and clear the air of the apparent “misinformation” given to the court. A factum filed at the murder trial said the society had “at all times” co-operated with the police and the prosecutor.

The society had been “aware” that the family court had awarded custody of Jeffrey, and his three siblings, to Bottineau and Kidman, and agreed with the decision.

How could an agency whose sole job is the welfare of children support rulings that turned over four innocent children to a pair of convicted child abusers, people wanted to know.

Surprising indeed since the society had a file on Bottineau, at the time, dating back 29 years to the death of her first of six children, whose injuries were described as Battered Child Syndrome.

As for Kidman, his file with the society at the time dated back 19 years to his conviction on two counts of assault causing bodily harm. But the damning information was never passed along to the three separate custody court hearings. Why?

One brief line in their factum explained the oversight by the government-funded agency. It read: “Unfortunately, its records were not checked.”

During the trial, a memorial was erected to Jeffrey in Greenwood Park. It was meant not only as a tribute, but also a reminder for everyone to be vigilant for “other small voices” who might be in trouble. Despite the belated concern from the community for Jeffrey, even in death he has suffered one final indignity.

His remains were cremated and given to his parents in a small, standard-sized container from the funeral home after a private service. Since his parents didn’t have an urn for Jeffrey, they decided to pour his ashes into an urn that contained the remains of another of their children, Gregory, who was stillborn, and cremated.

But there wasn’t enough room for the two sets of ashes in the teddy bear-shaped urn. So only part of Jeffrey’s remains fit into the urn containing the ashes of the other child.

The rest of Jeffrey’s ashes are in a box on a shelf at the east end home of his parents, both receptacles awaiting a final resting place. A mother, Amanda Reed, who came to the trial was inspired to write a poem that is now part of the memorial to Jeffrey in Greenwood Park. It reads, in part:

“In remembrance of a forgotten child, Who lived his short life locked away in hungry darkness, “Kept out of sight, out of mind, Starved of love, joy and kindness, “But smile now child, be free now child Your sweet face will live forever in our hearts.”

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

The Trial Continues...

The Globe and Mail

By TIMOTHY APPLEBY

Tuesday, January 17, 2006 Page A15

Five-year-old Jeffrey Baldwin was killed by his grandparents because they hated him, the accused couple's first-degree murder trial was told yesterday as the prosecution and defence launched their final arguments in Superior Court.

"Elva Bottineau and Norman Kidman disliked Jeffrey and [his older sister] to the extreme," Crown attorney Bev Richards told Mr. Justice David Watt, who is hearing the case without a jury. That "animus," she said, resulted in "severe child abuse over an extended period of time."

Jeffrey perished of septic shock in November of 2002, after spending most of his final months locked with that sister in a bedroom at the east-end Toronto Bottineau-Kidman home.

"Ms. Bottineau and Mr. Kidman knew that was going to happen," said Ms. Richards."This was a continuous downward spiral."

Lawyers for the accused presented an altogether different picture, with both defence camps contending that Jeffrey fell victim to extreme neglect rather than murder, which implies intent to kill.

But in one key regard, lawyers for the two accused diverged.

Anil Kapoor and Nick Xynnis, who jointly represent Ms. Bottineau, want their client acquitted not only of first- and second-degree murder but also of manslaughter, which generally means killing somebody by accident.

That's because her "mental impoverishment" is so extreme -- placing her within just 2 per cent of the population -- that she is incapable of realizing the consequences of her actions, Mr. Kapoor said.

That borderline mental retardation was documented as far back as 1970, when she faced criminal charges in connection with the death of one of her children, he said.

Then, as now, "she did not seem to have any real appreciation of the risks she took for others," Mr. Kapoor said, urging she be acquitted.

But Bob Richardson, Mr. Kidman's lead counsel, said his client bears some responsibility for Jeffrey's death and that the proper verdict should be manslaughter.

Taking a swipe at the Catholic Children's Aid Society, which approved the placement of Jeffrey and his three siblings in the couple's home after complaints of abuse, Mr. Richardson conceded that "out of a general state of indifference" Mr. Kidman had failed in his duty to protect Jeffrey.

But within the dysfunctional household, "it was Elva Bottineau's rules" that applied, Mr. Richardson said.

Mr. Kapoor argued that in examining "the appalling facts" of the tragedy, glaringly absent from the Crown's case against Ms. Bottineau is any proof of her intent to kill.

Not only did she call 911 on the day Jeffrey died, he said, but she wanted the boy alive rather than dead because of the welfare money he and his three siblings generated.

"She was abusive, and she wanted to abuse him, but she didn't want to kill him." Jeffrey died because Ms. Bottineau "doesn't see what we see," Mr. Kapoor contended.

The prosecutor rejected that thesis. When paramedics arrived at the house on Nov. 30, 2002, they found a near-skeletal five-year-old who was bruised, dehydrated and covered with sores and bacteria, she said, describing "a child who . . . was probably on the cusp of death."

As for intent, the fact Jeffrey and his sister spent long months locked up in their unheated bedroom offers proof that Jeffrey's death was not only intended, but also planned, Ms. Richards said.

Ms. Bottineau, 54, showed no emotion as defence and prosecution tussled. Mr. Kidman, 53, spent most of the day staring at the floor of the prisoner's box.

By TIMOTHY APPLEBY

Tuesday, January 17, 2006 Page A15

Five-year-old Jeffrey Baldwin was killed by his grandparents because they hated him, the accused couple's first-degree murder trial was told yesterday as the prosecution and defence launched their final arguments in Superior Court.

"Elva Bottineau and Norman Kidman disliked Jeffrey and [his older sister] to the extreme," Crown attorney Bev Richards told Mr. Justice David Watt, who is hearing the case without a jury. That "animus," she said, resulted in "severe child abuse over an extended period of time."

Jeffrey perished of septic shock in November of 2002, after spending most of his final months locked with that sister in a bedroom at the east-end Toronto Bottineau-Kidman home.

"Ms. Bottineau and Mr. Kidman knew that was going to happen," said Ms. Richards."This was a continuous downward spiral."

Lawyers for the accused presented an altogether different picture, with both defence camps contending that Jeffrey fell victim to extreme neglect rather than murder, which implies intent to kill.

But in one key regard, lawyers for the two accused diverged.

Anil Kapoor and Nick Xynnis, who jointly represent Ms. Bottineau, want their client acquitted not only of first- and second-degree murder but also of manslaughter, which generally means killing somebody by accident.

That's because her "mental impoverishment" is so extreme -- placing her within just 2 per cent of the population -- that she is incapable of realizing the consequences of her actions, Mr. Kapoor said.

That borderline mental retardation was documented as far back as 1970, when she faced criminal charges in connection with the death of one of her children, he said.

Then, as now, "she did not seem to have any real appreciation of the risks she took for others," Mr. Kapoor said, urging she be acquitted.

But Bob Richardson, Mr. Kidman's lead counsel, said his client bears some responsibility for Jeffrey's death and that the proper verdict should be manslaughter.

Taking a swipe at the Catholic Children's Aid Society, which approved the placement of Jeffrey and his three siblings in the couple's home after complaints of abuse, Mr. Richardson conceded that "out of a general state of indifference" Mr. Kidman had failed in his duty to protect Jeffrey.

But within the dysfunctional household, "it was Elva Bottineau's rules" that applied, Mr. Richardson said.

Mr. Kapoor argued that in examining "the appalling facts" of the tragedy, glaringly absent from the Crown's case against Ms. Bottineau is any proof of her intent to kill.

Not only did she call 911 on the day Jeffrey died, he said, but she wanted the boy alive rather than dead because of the welfare money he and his three siblings generated.

"She was abusive, and she wanted to abuse him, but she didn't want to kill him." Jeffrey died because Ms. Bottineau "doesn't see what we see," Mr. Kapoor contended.

The prosecutor rejected that thesis. When paramedics arrived at the house on Nov. 30, 2002, they found a near-skeletal five-year-old who was bruised, dehydrated and covered with sores and bacteria, she said, describing "a child who . . . was probably on the cusp of death."

As for intent, the fact Jeffrey and his sister spent long months locked up in their unheated bedroom offers proof that Jeffrey's death was not only intended, but also planned, Ms. Richards said.

Ms. Bottineau, 54, showed no emotion as defence and prosecution tussled. Mr. Kidman, 53, spent most of the day staring at the floor of the prisoner's box.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)